Writing an Academic Paper

The average piece of research is 10,000 words. That sounds like a lot, but I promise you that it flies by because academic writing is formulaic. I am not referring to the meandering, jargon stuffed sentences that often populate a piece of research. I am talking about the structure.

Below is a rough guide for someone new to academic writing. It generally works well for both qualitative and quantitative research and I'll do my best to flag any common differences.

1. Introduction: Framing Your Research

The introduction isn’t just the first thing people read. It’s the most important section—and the one you’ll likely rewrite the most.

Think of it as the 1000-word version of your entire paper. It should provide a miniature version of your argument, methods, and findings, while also setting the stakes. A strong intro:

- Poses your research question clearly (this can literally be your opening line).

- Explains why the question matters (i.e., what scholarly or real-world debates it speaks to).

- Summarizes your method and your main finding.

- Offers 2–3 big-picture implications of your work.

Optionally it also includes a roadmap of the paper’s structure.

**Framing is everything.** In an age of information overload, you're not just submitting an assignment—you’re selling an idea. Your job is to make someone care enough to keep reading. The way you present your question can hook your reader—or lose them. Good framing often involves: - Identifying which broader debates your project speaks to. - Explaining the puzzle or “weird thing” in the world that motivated your research. - Thinking hard about which angle has the broadest appeal—even if it’s not your personal favorite aspect of the project.

Starting to write is always the hardest part but the frame is your catalyst, If you're struggling to get started with the section, here are three models for the opening paragraph:

- Begin with the (framing)research question

- literally the opening line can be a question

- Begin with the academic stakes

- What are the core arguments of a debate you are responding to?

- An empirical example that illustrates the puzzle

- what’s the weird and timely event that is likely motivating your project?

2. Literature Review: What We Know (and Don’t)

The literature review serves three major purposes:

- It shows you understand the key debates and positions relevant to your topic.

- It helps justify your research by identifying a gap in existing knowledge.

- It lays the foundation for your theoretical model or hypothesis.

This does not mean you should regurgitate everything you've ever read. A good lit review:

- Is selective, not exhaustive.

- Clarifies which scholarly “camps” are debating the issue.

- Places your puzzle within these debates.

It needs to works at the right level of abstraction (ask yourself: what is this a case of?).

Done right, your literature review tells the reader: “Here’s what people have said. Here’s where they disagree. Here’s what they’ve missed. And that’s where my project comes in.”

3. Theory: Building Your Model

The theory section is your chance to go from “interesting puzzle” to “analytical contribution.”

Think of this section as model-building. You're offering a framework that helps explain your outcome of interest. A good theory section:

- Clearly lays out assumptions.

- Summarizes the model or argument early.

- Avoids excessive citations—this is about your thinking.

- May include a motivating example.

Don't be afraid to use subheadings for clarity.

Your theory doesn’t have to be flashy, but it must be clear. This section should provide the “why” behind your hypothesis—your causal story, your logical pathway.

For positivist work, it usually wraps up with the stating the set of observable implications, the hypotheses, that logically following from the theory.

4. Research Design: Showing Your Work

This section should answer a simple but crucial question: why should we believe your claims?

Regardless of method (qualitative, quantitative, mixed), this section should:

- Make all choices and assumptions explicit.

- Justify your case selection or dataset.

- Show how you’re measuring key variables (DV and IV).

- Explain why your approach adds value or differs from previous work.

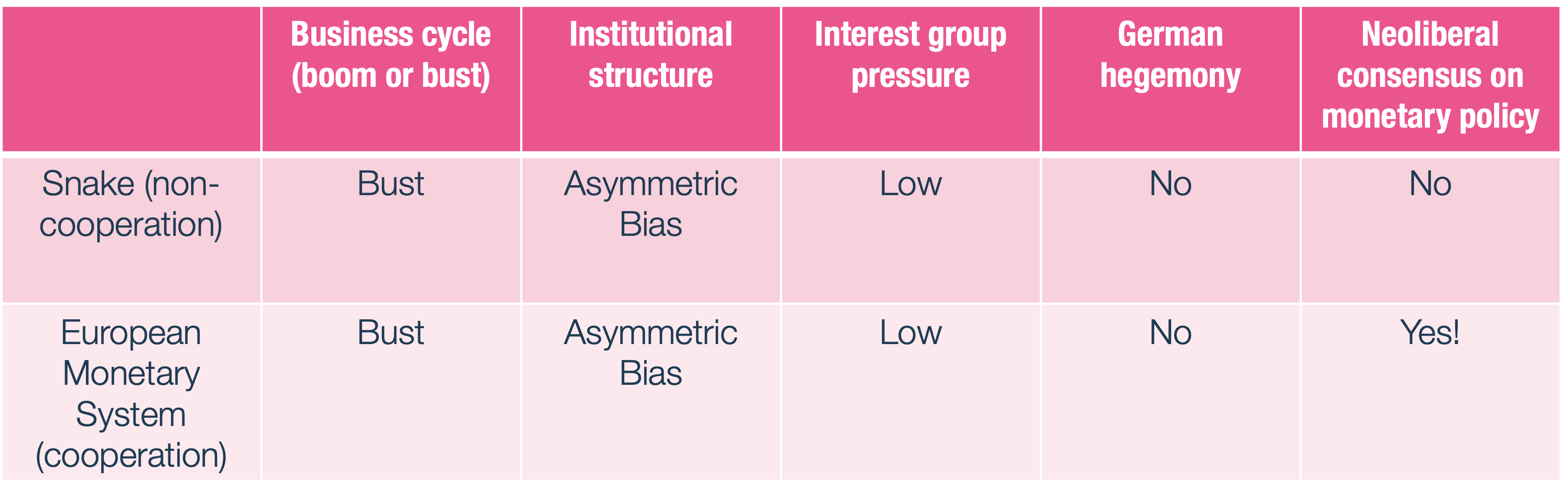

If you’re doing qualitative work (like case comparisons), include a case logic table that shows how each case varies along the relevant dimensions.

If you’re doing quantitative work, explain your modeling strategy, describe control variables, including where you are getting the data from and why you are including them, and accompany this with summary statistics.

Remember: clarity is more important than complexity. Your reader should be able to understand your design without having to read between the lines or be forced to look up something you are referencing.

5. Results & Empirics: Making the Case

This is the section where you show what you found. It needs to be consistent with your research design and explicitly tied back to your theory.

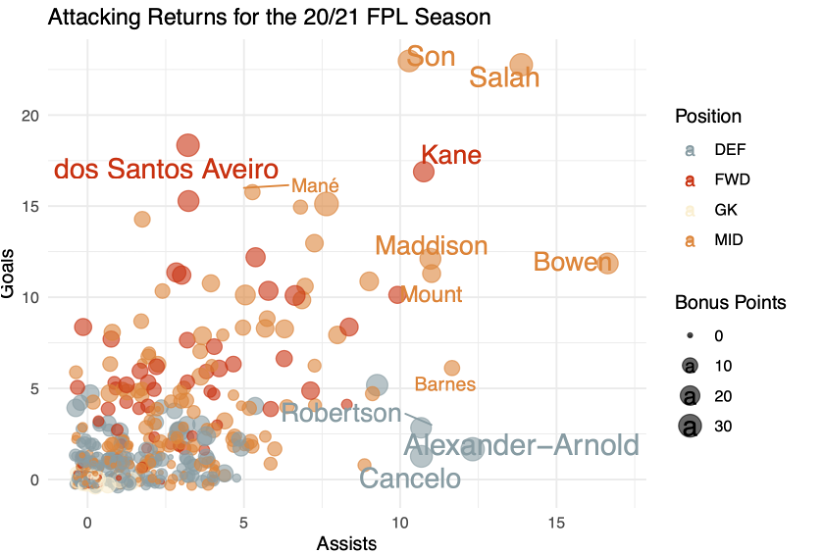

For quantitative papers:

- Start with descriptive plots, like the one above, where you just show the basic relationship between your IV and DV.

- Use [coefficient plots] to represent models visually.

- Always include confidence intervals.

- Consider using tools like margins in Stata or modelsummary in R to show substantive effects.

- Make smart use of titles and captions—tell the story in the visuals.

For qualitative research:

- Use a consistent structure across cases.

- Lay out levels of DV/IV clearly.

- Present compelling quotes tied directly to your hypotheses.

- Summarize findings case-by-case and then comparatively.

Whichever method you use, don’t just try to show your argument is right —test alternatives, acknowledge limitations, and be transparent.

It may even be useful to include a short discussion section on generalizability or edge cases. This is becoming increasingly common practice.

6. Conclusion: Why It Matters

Don’t sell yourself short. The conclusion is your opportunity to reflect, synthesize, and push forward.

A great conclusion will:

- Summarize your findings in 1–2 paragraphs (no more!).

- Revisit your big-picture implications.

- Suggest new research questions that follow from your work.

- Highlight any policy implications, if relevant.

- Note any limitations or areas where results were inconclusive.

Tie it all back to your framing. What did we learn? Why does it matter? Where should we go next?

Final Takeaways

Let’s recap the key principles for writing an academic paper:

You’re selling your project. That’s what framing is about.

The introduction is a 1000-word version of your paper.

Lit reviews are strategic, not encyclopedic.

Theory is model-building. Own that.

Keep your research design clear and methodologically honest.

Empirics need consistency.

Your conclusion should amplify implications, not just summarize.

10,000 words fly by.